Writing by NEFF Forest Scientist Colleen Ryan and NEFF Communications Manager Tinsley Hunsdorfer

New England Forestry Foundation (NEFF) is a member of the Forest Carbon for Commercial Landowners (FCCL) initiative—a group of conservationists, scientists, economists and commercial forest landowners—that recently set out to determine whether northern Maine’s commercial forestlands could sequester more carbon through improved forest management, and, if so, how much it might cost to incentivize landowners to implement.

The initiative commissioned a study to answer these questions, and has just released its results; ultimately, the study concluded the opportunity to address climate change by storing carbon in Maine’s commercial forests is large—if measured in metric tons of CO2 equivalents (a standard unit scientists use to measure carbon emissions and storage), its results are in the hundreds of millions.

The 54-page Forest Carbon for Commercial Landowners Report and its four appendices can be found in the NEFF website’s Publications section, and this blog post breaks down the highlights from the report’s methods, findings and recommended next steps.

Glossary

- Silviculture: The art and science of managing forests to meet desired goals, such as timber production and improving wildlife habitat.

- Additionality: the extent to which a given climate benefit would not have occurred in the absence of a proposed action.

- Continuous cover: a silvicultural system involving frequent, light harvests to improve the forest over time while also producing timber.

- Irregular gap: a silvicultural system involving the creation of small gaps to regenerate trees and create wildlife habitat while lightly thinning the residual stand, as in continuous cover. This is the practice most similar to Exemplary Forestry.

- Leakage: the spillover of in-forest carbon sequestration gains and losses from one economic market to another, given that the wood products we all use have to come from somewhere. If the United States or a region in the U.S. reduced the amount of wood it produced, any progress we claimed to make in reducing global atmospheric CO2 levels by storing more carbon in our unharvested trees would, in practice, be eclipsed by CO2 emissions from other forestry markets that increased harvesting to meet our unchanged demand for wood products.

- Regular shelterwood: a silvicultural system in which the overstory is removed in stages to allow new trees to regenerate under partial cover.

- Partial harvest: a management practice reflective of a portion of current practices, which removes 50 percent of timber volume every 50 years for the purpose of producing timber.

Methods

Researchers at the University of Maine used two computer models to evaluate the results of seven different land management practices over 60 years across northern Maine. The researchers didn’t make assumptions about which practices would perform best, and simply modelled established approaches—including leaving land unharvested—thereby allowing the model to select the “optimum” approach for carbon sequestration.

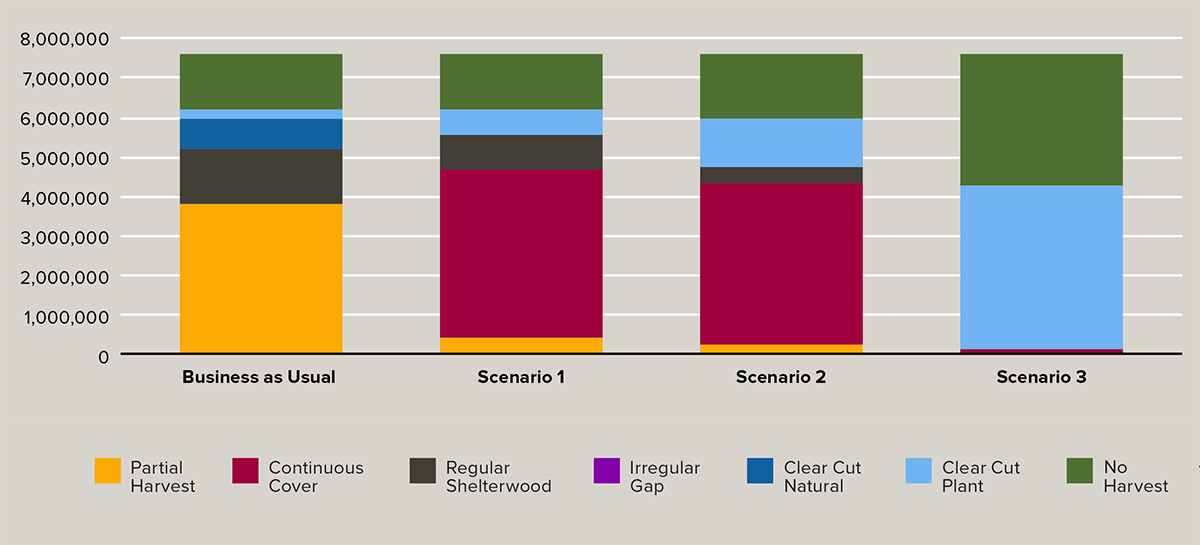

Most of the study area’s 7.6 million acres of forestland is privately owned and managed for commercial timber production. The modeled land management practices included intensive systems like clearcutting and planting, as well as more selective systems like continuous cover or irregular gap silviculture, which typically involve lighter but more frequent harvests. The models simulated forest growth and harvest levels under each system and then determined the best combination of management systems to use across the landscape to increase carbon sequestration for different management scenarios.

The study compared three possible scenarios to “business-as-usual” management (the silvicultural systems currently in use) to ensure any carbon sequestration benefits from improved management were truly “additional” (above what would occur under business-as-usual management). The project only considered scenarios that kept wood production at current levels to prevent leakage and to avoid negative impacts on rural Maine communities.

Forest Area by Management Type (Acres)

Results

The modeling found northern Maine’s forests are already sequestering a great deal of carbon under current management: 3.6 million metric tons of CO2e (MMTCO2e) per year. The report also identified two feasible scenarios that could increase sequestration above this level. In the first, which limited the use of clearcutting to current, relatively low rates but called for planting, sequestration was increased by 15 to 20 percent (to 4.1-4.4 MMTCO2e/year), primarily by increasing the use of uneven-aged management (that is, continuous cover and irregular gap, the system most like Exemplary Forestry—see “Next Steps” section).

The second scenario allowed the area managed with clearcutting and planting to double from current practice, increasing sequestration by 26 percent over business-as-usual levels (to 4.6 MMTCO2e/year). Because plantation silviculture is more efficient at producing wood, a greater area of the forest can be left unharvested, which increases sequestration overall.

Researchers included a third scenario only to show the theoretical maximum amount of sequestration that could be achieved while still producing current levels of wood; the FCCL collaboration does not suggest it is feasible to implement because of public opposition to clear cutting. In this scenario, 55 percent of the landscape was managed as plantations and 43 percent was unharvested, to produce a 41 percent increase in sequestration (5.1 MMTCO2e/year).

Researchers determined the cost of switching to the alternative management systems was $10-16 per metric ton of CO2e, which is substantially lower than other approaches to reducing carbon emissions, such as building new alternative energy systems, and exponentially more affordable than other carbon-capture techniques. The study concluded that providing incentives to landowners to change the way they manage their forests could be a cost-effective way to combat climate change, but did not recommend any landowners immediately implement the first or second scenario. More research and designing a program to provide the required incentives is needed before wholesale implementation is anticipated.

The report’s two feasible, successful scenarios involve maintaining or raising clearcutting levels from business as usual. However, as the report acknowledges, carbon capture is not the only priority to be considered when deciding how to manage forests. It is important to recognize that there are tradeoffs among carbon capture, increased production of climate-smart products, and protection of wildlife habitat and biodiversity, and the modeled scenarios are not intended to optimize for all of these values. A systems approach is required to address these multiple interacting values, and these kinds of modeling studies offer a fresh look at what is possible. NEFF’s science team looks forward to doing more of them and sharing their results until we fine tune the approach for northern Maine’s commercial forestlands.

Next Steps

“Overall the FCCL study should be viewed as a promising proof of concept—that Maine’s commercial timberland owners could be incentivized at competitive costs to sequester more carbon across the landscape and in [harvested wood products]. But the FCCL work… still relies on numerous simplifying assumptions that result in important uncertainties needing further exploration…” –FCCL Report Executive Summary, page 6

However, this study has accomplished something remarkable: showed that specific combinations of silvicultural approaches can have carbon benefits on commercial lands while still maintaining harvest levels, thereby making it possible for millions more acres to fully join the fight against climate change—alongside the public lands, private conservation lands, and family forests already doing so. The FCCL report was just the first step, however, and there’s more work to be done.

The report recommended refining and testing the study’s silvicultural practices and incentive programs, as well as assembling stakeholder coalitions for detailed discussions about incentive design and implementation—all of which could take place as part of NEFF’s USDA Climate-Smart Commodities program, given that commercial landowners are participating.

NEFF is also excited about determining irregular gap’s true potential through FCCL research. The benefits of irregular gap, the modeled system that’s most similar to Exemplary Forestry standards, are likely understated in the study due to modeling limitations. However, one of the study’s conclusions is that systems like Exemplary Forestry can be effective in increasing carbon sequestration on industrial lands without reducing harvest, and—when combined with other silvicultural approaches on portions of the landscape—that they can achieve this at a relatively low cost compared to other emissions-reductions approaches.

These systems also provide an option for increasing sequestration without increasing the amount of forestland managed with clearcutting. NEFF believes Exemplary Forestry represents the best approach for addressing climate change through forestry because it considers not just timber and carbon, but also the whole array of forest values, including wildlife habitat, biodiversity, recreational opportunities and ecosystem services.

Read the Forest Carbon for Commercial Landowners report.

Photo by Twolined Studio.