Forestry produces a wide array of benefits, from maintaining clean air and water to creating wildlife habitat—all while delivering a stream of sustainable forest products. In our spring issue of Into the Woods, bird experts Jeff Ritterson and Margo Servison from Mass Audubon describe how forestry can help turn around the trend of declining bird populations.

Writing by Mass Audubon’s Jeff Ritterson and Margo Servison

Ethereal. Flute-like. Haunting. Majestic. These are a few words commonly used to describe the song of the Wood Thrush. Henry David Thoreau wrote that the Wood Thrush’s song, “…affects me like music, affects the flow and tenor of my thought, my fancy and imagination. It lifts and exhilarates me. It is inspiring.” Indeed, a singing Wood Thrush is a comforting and familiar part of the New England forest soundscape, and a song many of us heartily welcome each spring. And with their speckled camouflage and lurking habits, they are more often heard than seen.

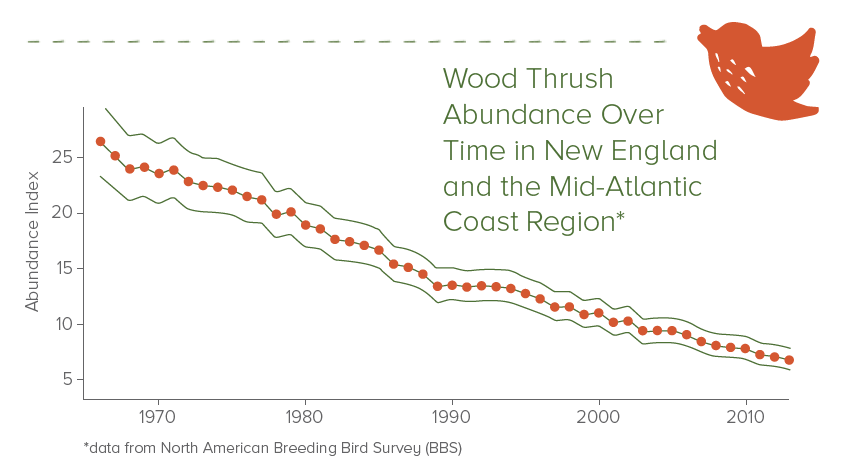

Unfortunately, these birds are being heard less and less. Data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), an organization that has been recording data on birds since 1966, shows Wood Thrush have declined in the northeast by roughly 80 percent—a loss of four out of every five individuals over the past 40 years. Even more alarming is that Wood Thrush aren’t alone. According to scientists from the North American Bird Conservation Initiative, 33 common bird species have lost over half of their global populations in the past four decades, and more than a third of all North American species (431/1554) are in dire need of conservation action.

Unfortunately, these birds are being heard less and less. Data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), an organization that has been recording data on birds since 1966, shows Wood Thrush have declined in the northeast by roughly 80 percent—a loss of four out of every five individuals over the past 40 years. Even more alarming is that Wood Thrush aren’t alone. According to scientists from the North American Bird Conservation Initiative, 33 common bird species have lost over half of their global populations in the past four decades, and more than a third of all North American species (431/1554) are in dire need of conservation action.

What is causing this staggering bird population crash? The answers are complicated and diverse, ranging from habitat loss and climate change to pesticide use, disruption from wind turbines, and predation from pet cats, to name a few. In an effort to maximize conservation efforts, scientists have begun prioritizing the most important factors impacting each species. In the case of the Wood Thrush, the linchpin is deteriorating quality of breeding habitat. Management efforts geared toward improving and restoring breeding habitat could contribute greatly toward reversing population declines.

What does ideal breeding habitat look like? Broadly speaking, Wood Thrush overwinter in Central America, and migrate to forests in the eastern United States to breed. More precisely, Wood Thrush require forests that are made up of multiple layers. From the ground up, decaying logs and leaves blanket the forest floor, and provide Wood Thrush a constant food supply of insects and invertebrates. Small shrubs and saplings provide laces to hide from predators. In the middle layer, young trees offer viewpoints, theaters for mating-call performances, and ideal nesting sites. And finally, mature deciduous and conifer trees create a continuous canopy, punctuated by a few small gaps where trees have fallen that allow sunlight to hit the forest floor and encourage growth in the understory. This forest type with many layers is often referred to as ‘old growth.’ It is one of the most rare forest structures found in New England.

Old growth forests were largely carried off the map in the 1700s and early 1800s as land was cleared for agricultural use. In the mid 1800s and continuing through the early 1900s, these fields were largely left abandoned. Forestland began to make a comeback. These regenerated, maturing forests make up the majority of New England’s forests today. Dominated by trees that are roughly the same age and size, these forests lack the variety and layers that species like the Wood Thrush rely on. Given sufficient time and periodic disturbances (i.e. localized weather events, beaver activity, or fires), some of these regenerating forests will transition towards old-growth forest. But critters like the Wood Thrush don’t have time to wait. They need breeding habitat now.

While unrestricted logging contributed to this situation, precise and sustainable forestry practices can turn it around. To get a sense of how forestry can help, picture the New England forest as it stands, with trees all the same size and age. By harvesting a portion of these trees, new gaps in the canopy are opened up. Sunlight hitting the forest floor encourages new growth, creating an understory of grasses, bushes, and eventually small saplings. Mature trees on the edge of this clearing are no longer competing with their neighbors for water and nutrients, and are able to grow more rapidly. In a fairly short period of time, a once homogenous forest now has a wider variety of structure and habitat. While the full transition is not immediate, practicing forestry can help accelerate this process and ultimately help out many species, including the Wood Thrush.

This bird’s eye view helps illustrate how forestry practices can strengthen habitats for birds. This is exactly what the Foresters for the Birds program works to promote and practice. Established by Audubon Vermont and the Department of Forests, Parks, and Recreation, Foresters for the Birds provides technical assistance to landowners interested in improving bird habitat. Through this program, trained consulting foresters work with landowners to evaluate existing habitat, identify possible improvements, and plan harvests accordingly.

With programs now implemented in several states, including Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, evidence shows that Foresters for the Birds is working. An initial study in Vermont shows that forestry practices have slightly increased the number of understory nesters (birds that nest in the understory) and gap specialists (birds that require openings in the tree canopy). As the forests continue to regenerate, scientists expect the positive effects to increase.

Bird-friendly forestry is also helping more than just birds. Birds like the Wood Thrush are considered an “umbrella” species—a species that relies on high-priority habitat that a wide array of wildlife relies on as well. By working to promote Wood Thrush habitat, other wildlife will be protected underneath this conservation umbrella.

In addition to wildlife benefits, the same forestry practices that open up new habitat can also protect water quality, promote forest health, and ensure long-term timber production. The Foresters for the Birds program helps educate and connect with landowners that may not otherwise be engaged with forestry practices. Most of the forests in New England are privately owned, which makes it critical for landowners to be empowered with the knowledge and tools to effectively steward the region’s forests and its residents.

In an effort to further connect with landowners, Mass Audubon is in the process of creating a demonstration site at their Elm Hill Sanctuary to showcase forest management practices for birds. Not yet open to the public, this site will create additional habitat for forest birds on the decline, and will also be used to educate professionals, landowners, and the public on the importance of forest management and its central role in the future of bird conservation.