This is the fourth post in NEFF’s blog series, Notes From the Field, which is designed to bring nature to you at a time when many people are sheltering at home. When it is safe to do so, staff members will offer a behind-the-scenes look at their current work and document interesting natural phenomena from forestlands protected by NEFF. We will also share retrospective stories.

Writing by Conservation Easement Manager Andrew Bentley

Protecting and enhancing forest wildlife habitats through permanent land conservation and responsible management is a key component of New England Forestry Foundation’s mission. Our spring 2020 Into the Woods newsletter article “Wildlife Cams and Corridors” features a vital example of such efforts as well as the use of remote wildlife cameras to document species living in our region’s forests. The article highlights Kevin and Nicole Knobloch’s 650-acre, NEFF-protected forestland, which is situated on a high ridgeline in the northwestern Massachusetts hilltowns of Charlemont and Rowe.

In this post, we will expand upon the importance of high-elevation water sources for wildlife in its home range or when using a protected area as a corridor between suitable habitats. Wetlands such as these come in a few types and often occur in saddles or depressions, or at seeps and springs at the headwaters of small streams, often on broader sections of a ridgeline. In the Knoblochs’ forest, a few perennial (always-flowing) brooks descend steeply to join together in “The Basin” as shown on United States Geological Survey maps to form Legate Brook, with the headwaters originating at springs and forested wetlands on the ridge above, including a small Red Spruce swamp where moose often find shelter. A couple of pools are found perched in depressions on the ridge high above the stream corridor several hundred feet below. Both have a vernal pool function, though only one seems to be a truly “vernal” pool, as the other holds water well beyond spring and summer.

What defines a vernal pool? It must meet a few criteria. There is typically no flowing outlet and therefore no fish population; the pool is (typically) only filled seasonally, by snowmelt and spring rain, lasting only for an ephemeral period and typically dries up by sometime in the summer. Most importantly, “obligate” species such as Wood Frogs, Spotted and other Mole Salamanders, or the unique crustacean known as Fairy Shrimp are documented successfully breeding in its waters due to the absence of fish. As mentioned, one pool on the Knobloch land seems to be a true vernal pool, lasting only through spring. I saw it inundated during a spring visit, but by autumn only leaf stains and a lack of understory vegetation evidenced its ephemeral existence. The other pool is typically filled beyond summer into autumn, and likely year-round during most years, but still seems to provide a vernal pool function since it has no outlet, and in it, I observed salamander egg masses in April. It was November when the Knoblochs and I first found it full of water, and when we returned in November of the next year, we once again found it inundated, and placed remote wildlife cameras on its edges.

This pool typically holds water even in autumn, likely fed by a slow seep, yet still has a vernal pool function.

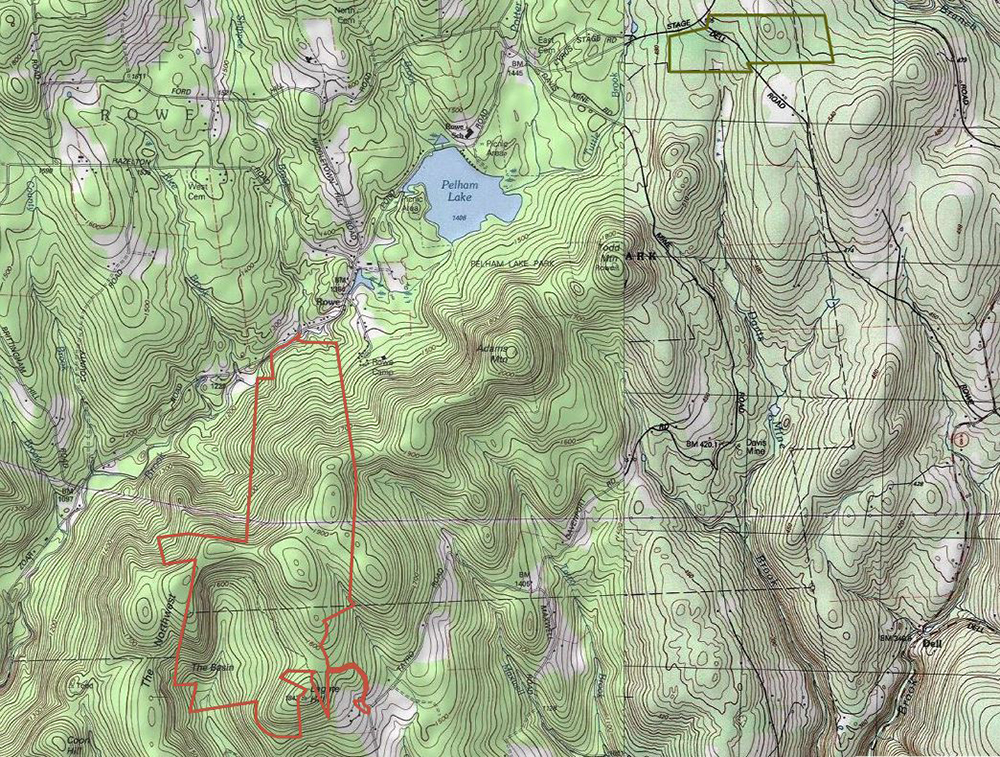

In the Knoblochs’ forest, wide-ranging wildlife species that depend upon large and unbroken woodlands find a home and can utilize the area as a corridor to pass back and forth between the Green Mountains of nearby Vermont and these rugged foothills. In fact, the area is mapped by the Staying Connected Initiative—which promotes landscape connectivity in the Northeastern United States and adjacent Canada—as a habitat node in the Berkshire Wildlife Linkage between the Green Mountains and the Hudson Highlands. This indicates the area is an important piece of the puzzle to facilitate wildlife travel and provide habitat in between these geographies. Their land is part of a more than 2,000-acre block of permanently protected forestland on this rural highland, bookended by their property on the west and NEFF’s own 120-acre Harriet Carpenter Read Memorial Forest two miles to the northeast through nearly unbroken woodlands. The forestland in between is protected by the Commonwealth, the Town of Rowe in its Pelham Lake Park, and the local Franklin Land Trust; additional unprotected forest parcels also enhance the assemblage. On Knobloch land, the ridge passes over Legate Hill and part of the evocatively-named “The Northwest,” meandering in fact to the northeast to pass over peaks like Todd and Adams Mountain on Rowe town land; to the south of the Knobloch conservation restriction (CR), it winds south over additional private forest land on Blueberry Peak before plunging in to the Deerfield River Valley.

The meandering ridge through Knobloch CR (red) up to NEFF’s own forest (green outline). Pelham Lake Park sits in between.

For wild animals, moving about their home ranges in search of food, or beyond those ranges in search of new territory or mates, is hungry (and thirsty) work. Curious humans wishing for a glimpse of this quiet world of animals on the move are wise to think about areas through which wildlife travels and where animals might stop for a break or to frolic.

First, wildlife biologists have found that mammals traveling between suitable habitats tend to favor linear landscape features that function as corridors, like defined ridgelines and riparian areas along streams, rivers, and wetlands. Wildlife, just like people, have essential needs for food, water, and shelter. Riparian areas very often provide all three when a natural vegetated buffer is maintained, and facilitate travel past adjacent incompatible human land uses which cannot serve as habitat. There is water of course, and often vertical structural complexity of vegetation along them, meaning layers of ground cover vegetation, mid-layer shrubs and young trees, and overstory trees, which can serve as potential food sources and cover from the elements and predators. Many animals even find conditions in these narrow areas suitable as a home, for example many bird species, certain amphibians, and river otters. Ridgelines serve as preferred corridors because they tend to be less impacted by manmade development than surrounding lowlands and gentler rolling foothills, and so can provide a link between suitable areas with human impact between them. Ridges often provide cover and shelter for safe passage when forested, but sources of food and water may be spaced apart. In places where food and water are situated along a ridge corridor, all three vital needs of wildlife are met and animals will frequently stop by them. This image of a White-tailed Deer on the Knoblochs’ land was taken on just such a defined ridgeline.

Therefore, if you are looking for signs of wildlife or a place to set up a remote wildlife camera, consider sources of nourishment and hydration that are likely to draw wildlife activity. The fruits and seeds of hardwood trees like beech, black cherry, and oaks are excellent sources of hard mast (seeds and fruit, think acorns and beech nuts) that are enjoyed, for example, by black bears, foxes, and turkeys. When you find striped maple in central and northern New England’s forests, look closely and it’s likely that you will see evidence of moose browse higher than your head. If you locate a vernal pool or wetland during your explorations, perched in a depression or saddle in the broader parts of a ridgetop, AND it’s within a hardwood stand or has shrub cover such as high-bush blueberry providing soft mast (fleshy fruit) or forage vegetation like grasses and sedges, the wildlife seeker’s senses should perk up. These areas where all three needs—food, water, and cover—converge are wildlife hotspots!

A playful young bear stopped to snack on sedges in the Knoblochs’ vernal pool before continuing on its way.

So far we have touched upon vegetarian food sources, but for a carnivore or omnivore species, vernal pools can provide some treats to draw them in. How? We have already touched on species breeding in vernal pools. Unfortunately for them, a passing mammal or bird of prey may not view the pool merely as a place for a refreshing drink of water, and the obligate residents are on the appetizer menu! Raccoons are known to predate egg masses and larvae, while hawks, owls, and other birds of prey will swoop down from their perches to snack on frogs and salamanders. Note the following Red-shouldered Hawk and American Bittern footage was provided by Phil Dowling.

Raccoons stop by to dig for a meal (amphibians?) at the Knoblochs’ vernal pool.

Wildlife Cams: Red-shouldered Hawk Eating Frog from New England Forestry Foundation on Vimeo.

Wildlife Cams: American Bittern Eating Frog from New England Forestry Foundation on Vimeo.

A final—and amazing—potential function of note in these wetland forest openings comes in winter when they are frozen over. Bobcats, who spend most of their time in solitude, are typically only spotted together when they meet to mate in February and March. After “swiping right,” they are known to meet up to wrestle and chase as a way to start getting to know one another. While I have not found this in research publications, the word of two respected tracker acquaintances and several engrossing remote camera observations on the Knoblochs’ land and other similar sites suggest that frozen wetlands provide an open area where this behavior takes place. Below are a few examples. Perhaps more research is needed, but in the meantime, I will be content to simply enjoy the enthralling glimpses that modern wildlife camera technology can provide us.

First, here’s video of a Bobcat pair passing by the vernal pool on the Knoblochs’ ridgeline.

Wildlife Cams: Bobcats in Northwest Massachusetts from New England Forestry Foundation on Vimeo.

Two Bobcats frolic on a frozen vernal pool similar to the Knoblochs’, on conserved forestland in western Massachusetts. Photo Credit: Sally Naser

A Bobcat pair meet by a thawing vernal pool in western Massachusetts as winter gives way to spring. Photo Credit: Sally Naser

Read More

Notes From The Field: Rocky Pond Community Forest | April 17, 2020

Notes From The Field: Early Signs Of Spring | April 28, 2020

Notes From the Field: What’s Making Me Happy | May 8, 2020

Notes From the Field: Resources for Wildlife on the Go | May 26, 2020

Notes From the Field: Problem Plants’ Spring Awakening | June 5, 2020

Notes From the Field: Race and the Outdoors, Through the Lens of Birding | July 10, 2020

Notes From the Field: Wildlife Signs and More While on Walkabout | August 6, 2020

Notes From the Field: Thinking Through Conservation’s Untold Origins While Driving to Conservation Sites | August 27, 2020

Notes From the Field: A Rare Turtle Sighting | September 25, 2020

Notes From the Field: Digital Field Tools for Work and Home | October 10, 2020

Notes From the Field: Winter Woodpeckers | November 19, 2020

Notes From the Field: Remote Monitoring and Satellite Imagery | February 18, 2021