New England Forestry Foundation’s Origins

In the 1930s and 40s, an eclectic group of foresters and outdoor enthusiasts grew concerned about destructive overharvesting on private New England forestlands. Much of the region’s once vast and ecologically rich forests had only just begun to regenerate after centuries of deforestation, and parcel owners often acted with an eye to quick profit or simply lacked an understanding of how to care for a forest.

In response, they decided to form a charitable organization devoted to the practice, teaching and promotion of sustainable forest management, and so the New England Forestry Foundation (NEFF) was born July 12, 1944 to help private forests thrive. Its land protection efforts kicked in soon thereafter when in 1945, NEFF accepted its first donated forest and opened it to the public.

See what conditions contributed to NEFF’s founding, and then take a journey through the organization’s history.

1860-1940: Setting the Stage | A Period of Rapid Change for Forests and Conservation

At the time of European colonization, forests covered 90 percent or more of New England. By the mid 1880s, however, vast stretches of this landscape-defining feature had been harvested and then cleared for agriculture; Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island were hardest hit, and lost up to 70 percent of their forests. While forests began to regenerate when farming moved west, little stood between vulnerable young forests and unchecked exploitation of natural resources.

In the early 1900s, inventive new technology like the pictured Lombard logging vehicle allowed for an increase in exploitative harvesting at a time when forests were already vulnerable. NEFF’s founders would go on to advocate for the responsible use of technology in forestry.

In the face of increasing pressure from concerned residents and scientists, the United States government began to take action to protect forests in the late 1800s. Congress passed the first law establishing a park on federal forestland in 1864, and in 1911 passed the Weeks Act, which allowed the federal government to acquire forestland and create national forests like the White Mountain National Forest of 1918. The executive branch also took positive steps: The U.S. Department of Agriculture established a Division of Forestry in 1881, the first federal forest reserve was set aside in 1891, and Gifford Pinchot as head of the Division of Forestry worked with President Teddy Roosevelt to establish the U.S. Forest Service in 1905.

While these actions proved effective at protecting certain high-priority forestlands and providing forestry expertise and services to large-scale corporate and public landowners, the federal government did little to improve the management of private, individually owned forestlands until 1937, when Congress passed the Norris-Doxey Cooperative Farm Forestry Act. It funded state foresters tasked with providing management and harvesting advice to landowners; it was also deemed inadequate by experts like New England Forestry Foundation founder Harris Reynolds, who felt that in place of piecemeal advice, landowners needed hands-on management services and long-term support that promoted forest health.

1944: New England Forestry Foundation Steps Onto the Stage

Reynolds and an eclectic cohort of foresters and outdoor enthusiasts had long been concerned about clear-cutting and destructive management on private forestlands in New England, where parcel owners often acted with an eye to quick profit or simply lacked an understanding of how to care for a forest. In response to the absence of effective government services, they decided to form a region-wide charitable organization devoted to the practice, teaching and promotion of sustainable forest management, and so New England Forestry Foundation was born July 12, 1944, to help private forests thrive.

Reynolds and partners at the Massachusetts Forest and Park Association designed a system of forest management centers for NEFF, in which trained consulting foresters would take responsibility for specific geographic regions and build relationships with local landowners.

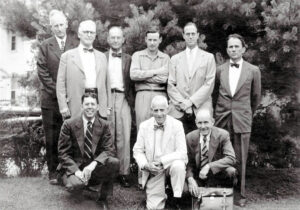

NEFF Directors meeting in New Hampshire (1945). Back row, left to right: Unknown, Hugh P. Baker, William P. Wharton, J. Milton Attridge, Nathan Tufts, James L. Madden. Front row, left to right: Farnham W. Smith, Ralph C. Hawley, Harris A. Reynolds.

1945: NEFF Opens Its First Forest and Hires Milt Attridge

NEFF forester Milt Attridge (left) and NEFF founder Harris Reynolds start a log down a log chute to the valley below.

When NEFF’s Lincoln Davis Memorial Forest opened to the public in 1945, it not only offered local residents an easily accessible place to enjoy woodland recreation—something of a novelty at the time, as the concept of town forests was quite new in the United States—but it also served as the first step in NEFF’s Exemplary Forestry work. As a demonstration forest, it allowed NEFF foresters to practice and start developing the in-house management style that has grown into NEFF’s current Exemplary Forestry standards.

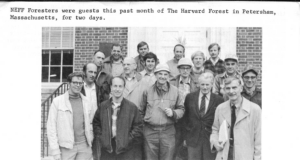

NEFF foresters visit Harvard Forest in Petersham, Massachusetts. Foreground, right: J.T. Hemenway. Front row, from left: C.B. Croft, H.T. Putnam, Sherman H. Perkins, J.M. Attridge, C.C. Richardson. Second row, from left: S. J. Rastallis, D.R. Poppema, C.M. Stewart, G.C. Knickerbocker. Third row, from left: F.A. Huntress, R.C. Boulanger, G.B. Bush. Fourth row, from left: K.E. Jones, W.A. Bean, S.B. Coville, J.C. MacMillan.

That same year, NEFF’s system of forest management centers really started to take shape when NEFF hired Milt Attridge, the organization’s first full-time forester and eventual Chief Forester. Attridge played a crucial role in NEFF’s early forestry work, and was well respected for his expertise and commitment to sustainability by fellow foresters and the communities in which he worked. Given his experience, Attridge was able to provide unique insight into the development of NEFF’s forestry program and its impact when interviewed for New England Forestry Foundation: A History.

Attridge on the initial pushback to New England Forestry Foundation’s approach:

“In the early years, the resistance to forest management under the Foundation came from the timber buyers, who did not understand selective cutting and were perfectly content to cut down ten small, healthy trees to get at one which they wanted to sell to the sawmill. They understand better now, and they understand our methods, and by and large accept them. It has become clear to them that they actually lose money by cutting smaller trees.”

Attridge on New England Forestry Foundation’s long-term impact:

“In more than 30 years, many lumber companies and mill operators that in 1944 would have done ruinous clear-cutting are now following conservation practices. With the equipment available today, had the bad practices of those early years continued, the very existence of our forests could well have been threatened. But thinking has kept pace with the improved equipment, with the result that the forests of today are actually in better shape than they were when the Foundation was started; and I think the Foundation should be given a good deal of the actual credit for this.”

If NEFF as a whole should be given credit for this, so too should Attridge and the teams of foresters he helped train.

1953: NEFF Publishes a “Review of Purpose and Progress”

As NEFF approached its 10th anniversary, its Committee on Finance distributed a progress report in the form of an open letter to the wider NEFF community. Its charmingly forthright opening paragraph is included below, and the entire letter can be viewed as a PDF.

“In 1943 the Massachusetts Forest and Park Association appointed a committee of woodland owners, representatives of leading forest industries and foresters to study the problems of small woodland owners. The New England Forestry Foundation is the result of that study. Started in 1944 with no money, no experience and as just an idea, it has developed in nine years into an organization with fourteen foresters in ten Management Centers, and has done work on 321,000 acres for over 1,000 owners, and has supervised the cutting of nearly 60,000,000 board feet of timber. There still remain on the lands of these clients 400,000,000 feet, worth over $7,000,000 at the average price of $17.65 obtained last year.”

The letter concludes that NEFF’s “experimental stage has been passed,” and the Committee on Finance declares the organization ready to train new foresters and expand its number of management centers. In total, NEFF would go on to hire and train 150 foresters to practice and teach sustainable management across New England.

1974: Townes Memorial Forest Opens

As NEFF’s forestry program continued to grow, so too did its network of Community Forests. The opening date of Townes Memorial Forest marks a time of transition for NEFF’s efforts to protect land through ownership—NEFF acquired about 10 forests per decade in the 1950s and 1960s, but that rate picked up significantly in the early 1970s and held through the 1980s and 1990s. NEFF took on 24 new properties in the 1970s alone, for example.

Located in New Boston, NH, the 551-acre Townes Memorial Forest is an interesting place to study glacial geology—NEFF history and the history of planet Earth, all in one spot. The property has a glacial kettle hole that was created when a large block of ice broke free of the retreating ice sheet and was later covered on all sides by outwash sands and gravels. Learn more on our Forest Stories page.

1989: NEFF Launches Conservation Easement Program

NEFF Stewardship Manager Beth Gula, Dave Sandilands of University of Maine, and Paul Swett of Wagner Forest Management team up to do a ground inspection of Sunrise Tree Farm, part of NEFF’s 335,000-acre Downeast Lakes Forestry Partnership easements, in 2018. Photo by NEFF Conservation Easement Director Andrew Bentley.

As earlier portions of this timeline show, land conservation in the United States was initially conducted through ownership, either in the form of public parks and forests or private property owned by charitable organizations like NEFF. Beyond NEFF’s own work, conservation easements expanded rapidly as a favored tool for land conservation throughout the 1980s. This followed on several revisions to the federal tax code in 1976, 1977, and 1980 that established a reliable framework for tax deductions for donations of conservation easements. Progress accelerated after 1982, when the development of the Uniform Conservation Easement Act by the national Uniform Laws Commission allowed for the adoption of consistent state authorizing laws.

While NEFF accepted one easement in 1977 and another in 1980, its full program launched in 1989 when NEFF acquired a 98-acre easement in Shirley, MA. It was followed by 37 easements in the subsequent decade, and NEFF now holds more than 150 easements that provide protection to 1.1 million acres of forestland.

1994: The Founding of New England Forestry Consultants, Inc.

NEFCo representatives were presented with the Forest Champion Award at NEFF’s 2019 Annual Meeting. Left to right: Fred Huntress, Dennis McKenney, Peter Farrell, Shaun Lagueux, Dave Kent, past NEFF Director of Forest Stewardship Chris Pryor, Sherm Small, Ryan Gumbart, Hunterr Payeur. Photo by Tinsley Hunsdorfer

By the early 1990s, the hard work of NEFF’s founders and foresters had paid off: the profession of consulting forestry was accepted and well-established in New England. This meant it was not clear that a nonprofit organization needed to continue providing forestry services directly to landowners. NEFF leadership restructured the organization, and NEFF’s consulting foresters became a new for-profit corporation that’s still hard at work in the region: New England Forestry Consultants, or NEFCo.

NEFCo and NEFF have remained close since this time of transition. NEFCo foresters manage most of NEFF’s lands, maintain NEFF’s forestry certification through the Forest Stewardship Council, and help NEFF with the design and implementation of new forestry initiatives. At NEFF’s 2019 Annual Meeting, NEFCo was presented with the Forest Champion Award for exemplary efforts in forest conservation.

2001: Pingree Forest Partnership Completes Record-breaking Easement

In March 2001, NEFF and the Pingree family completed the largest forestland conservation easement in the history of the United States. The project permanently protects 762,192 acres from development.

Cranberry Cove on Upper Richardson Lake, a part of the Pingree easement. Photo by Ben Pearson, courtesy of Seven Islands Land Company.

Three and a half times the size of Baxter State Park and larger than the state of Rhode Island, the Pingree easement conserves some of the most spectacular natural resources in Maine, including the Allagash Lakes and 16 miles along the St. John River. The forests support numerous active Bald Eagle nests, 24,800 acres of managed deeryards, 72,000 acres of wetland habitat, Maine’s most productive Peregrine Falcon nesting area, and at least 67 rare and endangered plant sites. The forests were—and are—healthy and productive thanks to decades of careful stewardship by the Pingree family.

NEFF and the Pingree family’s transaction set the stage for an explosion of so-called landscape-scale conservation projects. Many of these projects pair a forest management investor with a land trust that owns a conservation easement on the property, which results in a final arrangement similar to the Pingree project.

2004: Downeast Lakes Forestry Partnership Protects Crucial Landscape

The Downeast Lakes Forestry Partnership and NEFF’s 2020 Downeast Woods and Wildlife project ensure recreational opportunities in addition to conserving land and supporting economic activity. Photo by Lauren Owens Lambert.

Just a few years later, NEFF undertook a second ambitious easement project through the Downeast Lakes Forestry Partnership. This joint effort between NEFF and the Downeast Lakes Land Trust (DLLT) protected 339,000 acres in Maine’s easternmost county, and was designed to address both far-reaching conservation goals and the social and economic needs of the region.

Through this partnership, DLLT purchased and is managing 27,080 acres as the Farm Cove Community Forest, and NEFF purchased a 312,000-acre sustainable-forestry easement on the surrounding lands; NEFF also holds a 23,000-acre easement on the bulk of Farm Cove Community Forest. Strategically situated between 600,000 acres of conservation land in New Brunswick and 200,000 acres of state, federal, and Native American lands in Maine, the project contributes to the protection of more than 1 million acres across an international boundary. Public access is granted throughout the 339,000 acres, which include more than 1,500 miles of river and stream shoreline, 445 miles of shoreline on all or portions of 60 lakes, and 54,000 acres of productive wetlands.

From local loggers to boat builders, a variety of people depend upon this largely undeveloped landscape for their livelihoods and lifestyles, and seasonal residents and visitors turn to the area for recreation and rejuvenation—all while strengthening the local economy. The area is equally important for wildlife: It’s one of the most critical Neotropical bird breeding habitats in the northern area of the Atlantic flyway, and it is home to Pine Marten, Canada Lynx, and five percent of the state’s Common Loons.

2007: Hersey Mountain Forest Declared Forever Wild

The view from Hersey Mountain Forest. Photo by Kari Post.

Hersey Mountain Forest is unique three times over. It’s home to NEFF’s first carbon offset project, it’s NEFF’s largest owned forest at 3,200 acres, and it’s NEFF’s first property to have a large number of acres designated as “forever wild” rather than as managed forestland. A rigorous ecological assessment of the property recommended approximately 2,100 acres for protection under a wilderness conservation easement, which was recorded in 2007 to Northeast Wilderness Trust. The assessment found more than 20 natural communities, 42 vernal pools, 68 acres of old growth forest, and 513 acres of Significant Ecological Areas. These diverse habitat types make Hersey Mountain a true haven for wildlife.

2010: Regional Wildlands and Woodlands Vision Developed

Harvard Forest began developing its Wildlands and Woodlands vision in 2005, with an assessment of forest loss and the pace of conservation in Massachusetts. In 2010, the vision went region-wide, and clearly identified the need to ramp up the pace of conservation to protect forests’ benefits to New England residents. The NEFF Board of Directors formally endorsed the Wildlands and Woodlands vision in 2012, and then that same year hired a visionary forest leader to help the organization meet that mandate.

2013: NEFF Advances Mission With New Initiatives

UMass Amherst’s Olver Design Building serves as a demonstration of new and innovative wood construction technologies. The building integrates a structural system consisting of exposed heavy engineered timber and cross-laminated timber decking and shear walls. Photo courtesy of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Under the leadership of its new Executive Director, Bob Perschel, NEFF began to focus on innovative outreach, education and conservation initiatives in 2013. These initiatives furthered NEFF’s mission in new ways. First, NEFF launched its landowner outreach initiative in the MassConn Woods region to test how best to communicate with private landowners about sustainable forestry and keeping land healthy, and the Build It With Wood initiative followed in 2016.

This groundbreaking program promotes the construction of tall wood buildings with engineered cross-laminated timber (CLT), a sustainable material that can safely replace emissions-heavy steel and concrete. CLT was central to the construction of the John W. Olver Design Building at UMass Amherst, the Common Ground Charter School in New Haven, and a dormitory at the Rhode Island School of Design, among a host of other New England buildings that have already been built or are in the works.

2019: NEFF Publishes Exemplary Forestry Standards for the Acadian Forest

Like all NEFF Community Forests, Reynolds Family Forest in Downeast Maine is managed with Exemplary Forestry. Photo by Lauren Owens Lambert.

NEFF has owned forestland since 1945, and over time, the science-based sustainable forestry NEFF has chosen to not only practice on its own lands but also test and improve upon has become its own house style. In the 2010s, NEFF foresters and ecologists began to codify this management style and place it into a landscape context so other landowners could make use of it.

Exemplary Forestry is a forest management approach that prioritizes forests’ long-term health and outlines the highest standards of sustainability currently available to the region’s forest owners for three key goals: enhancing the role forests can play to mitigate climate change, improving wildlife habitat and biodiversity, and growing and harvesting more sustainably produced wood. Exemplary Forestry also lays out specific and measurable practices to achieve these goals simultaneously, and takes the wider landscape into account when determining how to manage specific land parcels.

In 2019, NEFF published Exemplary Forestry standards for northern New England’s Acadian Forest region, as well as an accompanying 27-page report, “Exemplary Forestry for the 21st Century: Managing the Acadian Forest for Bird’s Feet and Board Feet at a Landscape Scale.”

The climate-mitigation benefits of Acadian Exemplary Forestry standards make up the bulk of NEFF’s 30 Percent Solution, which combines the organization’s work on forest conservation, Exemplary Forestry, and sustainable wood buildings to offer an opportunity to put the region’s forests to work on perhaps their most important mission ever—maintaining a safe and healthful climate.

NEFF’s analysis suggests this holistic approach to addressing climate change could keep more than 646 million metric tons of CO2 out of the atmosphere over the next thirty years, with the practice of Exemplary Forestry contributing 542 million metric tons.

Those 646 million metric tons represent nearly one-third of the total energy-related CO2 emissions—meaning, emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels—New England needs to eliminate over the next several decades.

2020: NEFF Conserves 9,150 Acres Through Downeast Woods and Wildlife Project

Two of the properties included in NEFF’s Downeast Woods and Wildlife project are located along the Dennys River, which provides ideal habitat for Maine’s endangered Atlantic Salmon. Photo by Lauren Owens Lambert.

NEFF had embarked on an ambitious conservation project called Downeast Woods and Wildlife in 2018, and when the project came to a successful conclusion in December 2020 despite the tumult of COVID-19, it shifted the geography of NEFF’s conservation legacy: Downeast Maine, with its fog-wreathed coastlines and deep green-and-grey forests, became home to most of this century’s large-scale NEFF conservation work to date.

NEFF ultimately reached three times the original conservation goal for the project, which means 2020 added more acreage to NEFF’s network of Community Forests than any previous year.

The initial aim of the Downeast Woods and Wildlife project was to purchase and protect forestlands along the winding and sun-dappled Dennys River, whose waters—kept cool and clean by riverside forests—provide critical habitat to Maine’s endangered Atlantic Salmon population and other cold-water fish.

The project had its first major success in summer 2018 when NEFF purchased the 1,160-acre Reynolds Family Forest, and NEFF went on to take ownership of a second Dennys-adjacent property—the 2,200-acre Venture Brook Community Forest—in December 2020.

This alone would have been enough to call the project a success, but in October 2020, NEFF received two donated Downeast Maine properties: a 2,690-acre parcel along Holmes Stream in Washington County and a 3,100-acre parcel near Egypt Bay in Hancock County. Now called Holmes Stream Community Forest and Frenchman Bay Community Forest, they also stand to benefit wild animals, just ones with feathers rather than fins.

2021: NEFF Publishes Exemplary Forestry Standards for Central and Transition Hardwood Forests

The Scarlet Tanager is a member of one of three groups of umbrella wildlife species for Central and Transition Hardwoods Exemplary Forestry.

After completing the Acadian Exemplary Forestry standards in 2019, NEFF turned its attention to the woodlands of southern New England and the creation of equally powerful standards for this significantly different setting. NEFF went on to publish Exemplary Forestry standards for Central and Transition Hardwoods in 2021, and they account for the five most common and economically important forest types in the Central and Transition Hardwoods region: Oak-Hickory, White Pine, Oak-Pine, Hemlock and Lowland/Riparian Hardwood.

Hardwood forest types play a bigger role in these standards because southern New England represents the transition area between the Acadian Spruce-Fir forests to the north and the deciduous (hardwood) forests to the south.

NEFF’s two sets of standards have the same broad framework, but the details within that framework look pretty different from one set to the other. Not only do climate zone, elevation, and forest types shift as you move from northern Maine to coastal Connecticut, but so too do human-controlled factors like forest stocking levels. Learn more.

2022: NEFF and Partners Receive a $30 Million USDA Climate-Smart Commodities Award

Credit: Michael Perlman.

NEFF has experienced a few sea changes in its history, where the organization accomplished something so momentous it changed not only how the wider world saw NEFF, but also how NEFF’s immediate community, Board of Directors and staff saw themselves.

Once, NEFF wasn’t considered the sort of organization that could conserve 760,000 acres of forestland in one fell swoop. Once, NEFF didn’t seem the sort of place to produce groundbreaking forestry standards capable of mitigating nearly a third of the region’s necessary CO2 emissions-reductions. Once, NEFF winning a $30 million grant to implement climate-smart forestry wasn’t even on the horizon. And yet—NEFF has accomplished all of this, and is still looking for more ways to make a difference.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Partnerships for Climate-Smart Commodities program awarded $30 million to NEFF and its partners in September 2022 to help forest landowners implement climate-smart forest practices that also protect ecosystem health and biodiversity. The award funds a five-year pilot project organized around three broad goals and areas of work:

- Climate-smart forestry incentives for practices that store more carbon in working forests for a group of forest landowners across all six New England states, including on large commercial forests, smaller family woodlots and First Nation woodlands

- Market-building for climate-smart forest products, with a focus on mass timber construction

- Monitoring, verification, and reporting to document and ensure additive carbon benefit

NEFF will work to leverage the USDA’s generous investment to accomplish its 30 Percent Solution, which calls for significantly expanding the use of NEFF’s own approach to climate-smart forestry—Exemplary Forestry—across the managed portion of the 32 million acres of forestland that spans New England. This makes the pilot project both an important first step and an opportunity to gather lessons learned for when NEFF moves to this wider landscape.